In HIS 3310, how you communicate your findings is essential. We will explore the latest tools historians use to share their research with diverse audiences. Click any link below to read more!

Research

Research is about discovery. For most historians, it is a joyful experience precisely because it is an intellectual journey of the unexpected. You never know what leads you might find; or, you might discover that a particular source has yet to be explored by others and is ripe for analysis. Even if you are working on a topic, or a set of sources, that are well known to most historical researchers, you bring a unique perspective and analytical approach that is all your own. Why? Because historical research is by nature a personal endeavor. Thus, your narrative and analysis are uniquely your own.

As simple as this sounds, a lot of thought and planning goes into historical research. Which content management tools do I use? How will I record my information? Does the archive place limits on what I can bring with me? How do I organize my photographs? Which books in my field should I read? Is there a danger of reading too much (and not getting to work on writing or producing my findings)?

- Our History Dept. liaison at Belk Library, Breanne Crumpton, created this a useful Google Doc handout.

- For an easy-to-reference list of History-focused journals and databases, visit the Belk Library History portal.

It is vital to read broadly and then find the key works of research that exist on your topic. You want to figure out the spaces you can navigate that will allow you to say something new about your subject. Your goal is to spark a conversation among historians, which sometimes means pushing back on established narratives. As daunting as this sounds, no one wants to read a “re-tread” on a given subject. Once you have found your space, it’s time to put your research and primary sources to good use!

How do I get started? Read, read, and read about your subject/topic … and then begin formulating questions that may or may not become the research question for your project.

Historiography is the study of the discipline of history. Its study requires you to consider how interpretations of a particular event change over time. When analyzing, discussing, or writing about historiography, you are using secondary sources— not primary sources. This means working with articles and books written by historians in order to understand how interpretations of the past have evolved over time, and sometimes how historians enter into debates (even heated ones at times!) over sources and interpretations.

OTHER RESOURCES

- NC State’s Department of History has an old, a bit dry, but excellent “Step-By-Step Guide” on how to get started with historical research.

- We will refer to this page on a frequent basis.

- A similar webpage comes from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts course on Historical Methods & Literacy.

- Although somewhat focused on environmental history, the personal website of historian William Cronon offers a nice introduction to historical research, guiding students from the initial research question stage to working with specific sources (photographs, maps, interviews, etc.).

- Make sure to explore the various menu items (located on the left) on the “Introduction to Historical Research” webpage of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries.

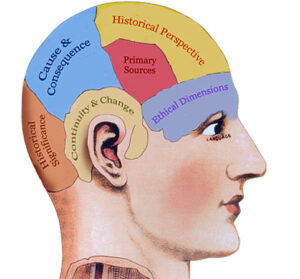

Historical Thinking

What does it mean to think historically?

Historians, like many other social scientists, approach their investigations with a skill set that is part of their training and helps define their field. This is why developing your “historical literacy” is an important step towards your growth as a historian. It means entering a conversation with texts and other historians. To put it another way, historical literacy is about gaining a deep understanding of historical events and developments through an active dialogue with historical texts.

There are many useful guides to historical thinking. You can easily search “historical thinking” and find dozens of websites dedicated to this subject. One of the more useful guides comes from Teachinghistory.org’s webpage on “What is Historical Thinking?” It outlines five elements of historical thinking that are all integral to understanding how we know what we know about the past:

- Multiple Accounts & Perspectives (requires):

- using multiple sources to get as accurate a picture as possible of events in the past

- working with multiple accounts, and learning to analyze and synthesize them.

- recognizing that no single account, written from one perspective, captures the complexity of the past

- Analysis of Primary Sources

- Primary sources are original documents and objects created at the time under study. They are vital to reconstructing the past.

- We must learn how to read, question, contextualize, and analyze primary sources.

- We look for points of agreement and disagreement between the two contrasting accounts.

- Primary sources need to be questioned and read closely.

- Sourcing

- Sourcing is about identifying and asking questions about the origin of the source, the author’s purposes and perspective, when the source was created (and for whom), and about a source’s trustworthiness.

- Context

- Historical context is about locating events and sources in time and space … and asking the necessary questions to do so.

- Claim-evidence Connection

- Historical narratives must be supported by evidence. History isn’t fiction. Even if we sometimes make educated guesses to fill in the gaps, our arguments and narratives are based on evidence.

- Truth claims need to be supported by evidence.

Historical Thinking Skills: Other, related elements (causation, significance, change over time, and corroboration, for example) are central to the historical profession. The American Historical Association (AHA) produced a primer for students and educators alike. As the world’s largest professional association for historians, the AHA possesses an out-sized influence on how historians define their work, re-think the nature of the profession, and articulate their contributions to society.

Here are the five key skills outlined by the AHA (with hyperlinks to the main AHA webpage) and that any student must develop in a history classroom:

Historical thinking is complex, but it is also vital if we want to promote a society of readers, thinkers, and informed citizens. If you plan on working with students in your career, just remember that historical thinking is NOT separate from the content we want students to learn; instead, it is the skill set that will help students master their understanding of the past.

SOURCES

- AHA. “Historical Thinking Skills: What Skills Should You Have When You Leave a History Class?” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/the-history-of-the-americas/the-conquest-of-mexico/for-teachers/setting-up-the-project/historical-thinking-skills#1.

- Andrews, Thomas, and Flannery Burke. “What Does It Mean to Think Historically?” Perspectives on History, January 2007. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2007/what-does-it-mean-to-think-historically.

- Historical Thinking Project. “Historical Thinking Concepts.” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://historicalthinking.ca/historical-thinking-concepts.

- Teachinghistory.org. “What Is Historical Thinking?” Accessed December 21, 2020. https://www.teachinghistory.org/historical-thinking-intro.

Writing

Does the following quote sound familiar?

Writing is stressful. Sitting in my computer chair my neck and shoulder muscles almost immediately tense up as I dig around in my brain for the best phrase or even any coherent string of words, whether I am writing an essay like this one, a book chapter, a letter of recommendation, or an email message to a friend. Writing is time-consuming.

In an article published in 2010 in Perspectives in History, “How Writing Leads to Thinking,” UCLA professor of history Lynn Hunt distills the frustrations and joy of writing. For some, words come naturally but strong ideas, and provocative thesis arguments, are a bit of a struggle. For others, it is quite the opposite. Maybe you are one of the lucky few whose ideas and words flow beautifully in tandem; or, maybe you are one of the unlucky who struggles with both.

This semester, you will likely discover which of the four categories you might fall under. Ultimately, though, writing is inherently a thinking process. This is especially true in the field of history, where research becomes an exhilarating endeavor that bears a vast amount of notes and sources, while writing can seem overwhelming when trying to put those notes and sources into a coherent product.

Hunt’s article offers several suggestions, but two stand out: be consistent with your writing (a little bit each day goes a long way!) and be patient (learning to write well is a lifelong endeavor). I hope HIS 4100 becomes an important step in your journey as a historian, and, maybe, just maybe, it becomes the invigorating habit Dr. Hunt describes in her article:

Writing means many different things to me but one thing it is not: writing is not the transcription of thoughts already consciously present in my mind. Writing is a magical and mysterious process that makes it possible to think differently.

RESOURCES

- “How to Write a History Research Paper” from Carleton College is a basic primer on getting started with a major research paper.

- Writing a Good History Paper is a useful webpage from Hamilton College (NY), with a list of reasons why editors/advisors/professors leave negative comments on history papers and tangible steps to submitting an effective (senior) research paper. [.pdf version]

- Take time to browse the excellent and thorough guide entitled “Reading, Writing, and Researching for History” from Bowdoin University.

- Writing Resources from Harvard University offers links to many useful resources for historical writing.

CITATIONS

- Chicago Manual of Style (simply known as “Chicago style”) is the standard for the field of history. It is sometimes known as “Turabian style,” for University of Chicago dissertation guru Kate Turabian. All footnotes/endnotes and bibliography (or works cited page) must adhere to Chicago style according to the type of source you are citing, and following the conventions for the notes & bibliography system.

Digital Tools

The “digital shift” of the last two decades has raised interesting possibilities and questions about how we can research, write, learn, and teach about history. Today, historians reach audiences in multiple ways that use some form of technology (websites, digitized collections, e-books & journals, social media, online courses, and webinars, and more). Whether your career path involves education, curriculum development, museum studies, government or NGO work, or other sectors, you will deal with two basic questions: “How can audiences engage with the past online?”, and “How can historians make the best use of digital tools and new media?”

For a list of digital resources for historians, check out the AHA webpage for getting started with digital history.

There are many websites out there that curate a collection of digital tools and resources for historians. Although many tools (and links) wind up “dead,” it’s useful to become familiar with a few, such as this one from the University of Washington, another from Sam Houston State University, and yet another from the University of Arizona. You can also find enthusiasts’ sites that compile digital history tools and resources from around the world, such as Awesome Digital History, and a comprehensive personal website from historian Jeff McClurken (check out his ongoing compilation of digital tools and papers presented at history conferences and workshops).

For those interested in teaching 9-12 social studies, an oldie (but goodie) is the website Teachinghistory.org and its section devoted to the Digital Classroom. Here, you will find teaching strategies and over 70 reviews for digital tools under Tech For Teachers, which include steps on how to get started and examples of history lessons.

Campus Support

The History Department faculty not only bring a wealth of expertise and knowledge in their fields, they genuinely like to help students and see them succeed. Although your instructor (Dr. Rwany Sibaja) is your main support and resource, you have extra support as well:

- Contact your program advisor at any time for academic, career, personal, or any other support you need this semester. For History majors, these are your advisors:

- History Education: Mrs. Jennifer Morris

- Multidisciplinary; Applied & Public History: Ms. Amy Hudnall

- History (BA): Mr. Jonathan Billheimer

- There are two safe and quiet writing spaces available to you in the History Department in Anne Belk Hall: the History Lab (located in a room near the faculty lounge; contact Haley Herman for Spring 2023 hours), and the mini-conference room outside in ABH 220 (outside of Dr. Sibaja’s office), which is open most days from 8:30am-2pm.

Appalachian State University also offers support for students in various capacities. Although you might be familiar with these resources, the following are some links and descriptions you might find useful:

- The University Writing Center is located in Belk Library. It is a free resource available to all App State students. Consultants are experienced writers who work with students one-on-one to assist with any aspect of the writing process. Consultants provide assistance with writing at all stages and in any subject matter.

- Belk Library offers a variety of support services. Their Research Advisory Program is particularly useful in the early stages of any project; staff can help you find the research sources you will need for your topic (not just on-shelf books and journals in JSTOR!).

- The History Dept. liaison in Belk Library is Breanne Crumpton. Contact her if you have specific questions.

- Instructional Technology is located (conveniently) in Anne Belk Hall on the first floor. You can access the entrance from the rear of the building facing Varsity Gym. IT Services is the central support structure for assisting students with computer technology. The Technology Support Center handles both software and hardware issues for student personal computers, which is a fantastic and cost-effective way to keep your computer running smoothly. Support may also be contacted in a number of other ways at: https://support.appstate.edu/students.

- The Career Development Center serves all students, as well as alumni, in future professional planning. CDC services include resume and cover letter reviews, career coaching, job and internship search assistance, and other tools to achieve life and professional success.

- The Office of Student Affairs offers even more services. Make sure to check their COVID-19 update page for the most up-to-date information: https://studentaffairs.appstate.edu/student-affairs-covid-19-response

Professionalism

Regardless of your major, your training at App State has revolved around research, critical thinking, a consideration of multiple perspectives, effective communication, causality, reading sources or interpretation, and citing the work of others. Consider how to carry all of these skills into your future career as habits of mind. Whether you become a faculty instructor, law office research associate, editor or writer for a publishing house or newspaper, technology associate for education-related projects … the skills you practice in HIS 3310 will serve you well.